When I started working on this blog, I thought I’d alternate between Lessons from current designs and more theoretical, academic-ish stuff. However, I’ve tended a lot more towards the academic style: it’s sort of what I default to when I sit down to write. It also means it’s mostly been enormous articles. So today, I’m doing a more anecdotal one, and hopefully it will be much shorter. Hey! No laughing!

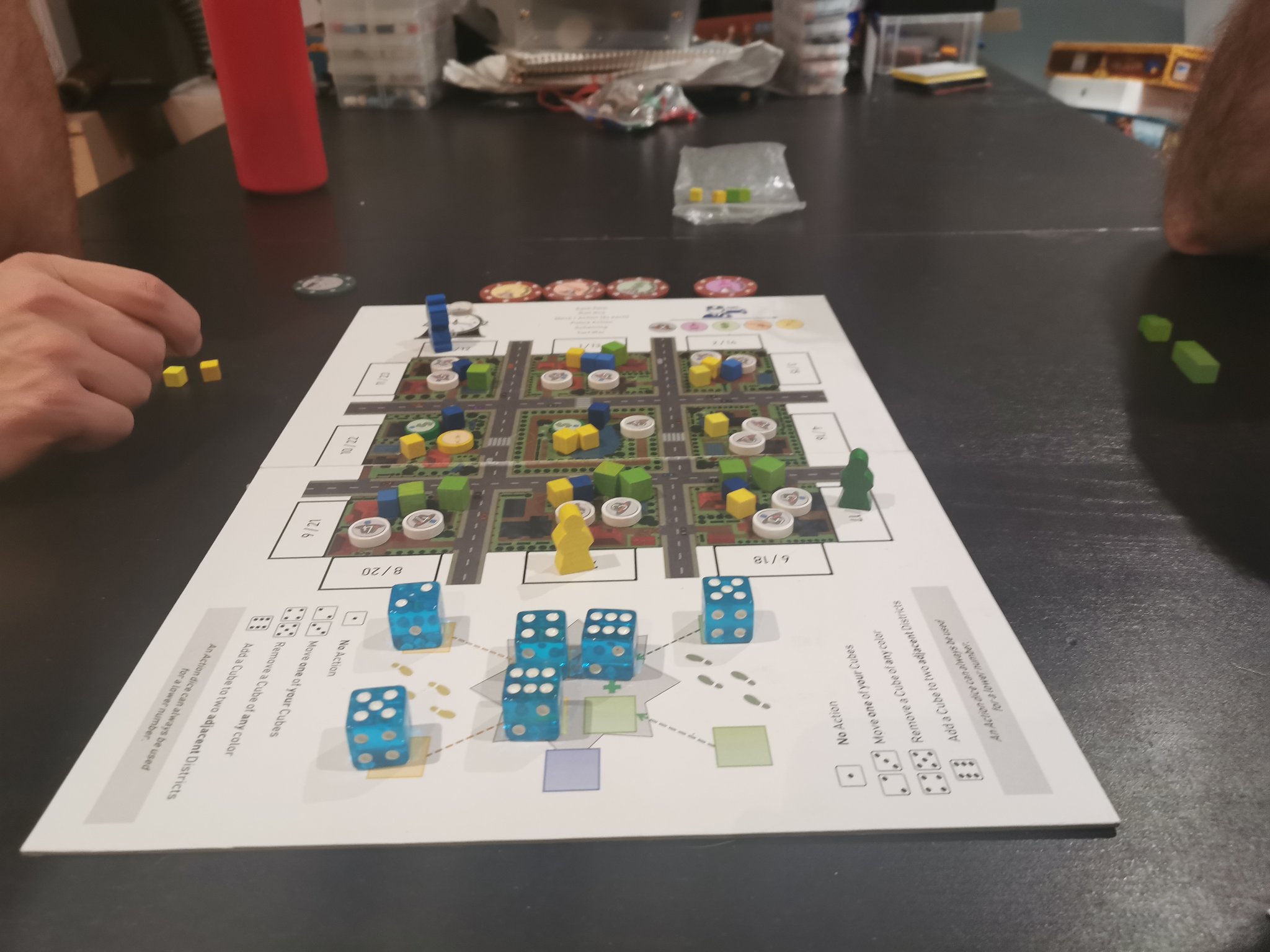

So quick overview: With a Smile and a Gun is a 2-player dice drafting game of area control. It is set in the Prohibition Era and puts the heads of two rival crime syndicates head-to-head to control it. It’s named after a famous line by Al Capone: “you can get far in life with a smile, but you can get a heck of a lot farther with a smile and a gun”. I think it sounds awesome. It’s the third game I’ve started working on, and I’ve learned a LOT of stuff along the way.

Lesson 1: Make the game’s core solid before playing with special abilities. If special abilities are ways for players to break the rules, it makes sense for you to design them after the rules are set. With WS&G, I knew I wanted a layer of variability and for the players to have special abilities which varied from game to game, so I added it from the get go. In the end, the core of the game worked, and hasn’t changed much since, but I only knew that when I ran 3 back-to-back playtests without the ability, after 10-15 playtests with them. Even now, with this game I know like the back of my hand, any change to the core mechanism means a few tests without the abilities.

Lesson 2: Decisions are good, but they take time. For the longest time, winning a district gave you a choice between two scoring tiles (which were different set collection things), and second place took the leftover one. It seemed like an interesting choice to make, but it also meant the scoring phase took as long as the action phase, but wasn’t half as interesting. I therefore changed it to be MOSTLY straight up point values, and a few of the set collection tokens. Most of the time, you’re taking the highest value, but once or twice a game, you’ll have a tougher decision. Once or twice a game is fun, tense moments, but thirty times a game isn’t.

Lesson 3: Value of a majority for 2-player games. When I made the switch to point values, they were worth 5-10, and most of the special tokens were majorities players were competing for. At first, I calculated that if there were 5 tokens available, you needed 3 to get the majority (ish, there are ways to get rid of some), and so set the value at 21: it’s average if you need 3 tokens to snag it up (7 points each), but if you can take it in two, it’s incredible. In practice though, what happened was that every single token of that type became worth 21 points: whether you controlled the majority and needed to block your opponent from catching up, or the other way around, you were fighting for that 21 point swing. On the last round, if you were tied 2-2 and the last token showed up, it was worth more than twice as much as any other token. Therefore, I gave them values of 8-10-12, more in line with the other tokens, but a bit stronger because they weren’t sure things.

Lesson 4: Piles of 10. When I made the switch to point value tokens, I went with values from 5-10, and majorities worth 8, 10, and 12. I liked that it gave me 6 different amounts for straight points, which led to a lot of variety. But at the end of the game, scoring often took a lot of time, because players couldn’t do the go-to scoring method: piles of 10. Not enough smaller values meant needless math. I switched it to values between 2-6, which really didn’t change much gameplay-wise, but now calculating scores at the end of the game takes a fraction of what it did.

Lesson 5: The impact of presentation. With those majorities, one thing that came up is that if your opponent gets ahead, there’s no point in you catching up. Therefore, eventually I added a second place value so you at least wanted to get one (or block your opponent from having it): instead of 10 points, it was 20 for first, 10 for second. It meant throughout the game, the competition was tough: either you were fighting for first place, or fighting to gain one of those tokens to get second place. And since those majorities are played on, at most, 6 tokens, it was always tight. However, players didn’t really like the “consolation prize” aspect of the second place. It never felt nice to get.

Since I loved the mechanism, I just re-branded it. Instead of 20 for first, 10 for second, I added Monopolies: majorities are worth double if your opponent doesn’t have one. Mechanically, it’s still the same thing: it’s a 10 point boost for first, and a 20 point boost if you’re alone in it. And that part, players LOVED. Someone even called it innovative –which of course I didn’t correct, finally somebody recognizing my genius! All of which came from this little bit of presenting those same bits from a different angle.

Of course, I learned many other things while working on this game, but these felt like the more universal. Hopefully I can remember to make this sort of thing in the future, and make the “Lessons learned” a series of sort! Hopefully you found something in there that can help you!

2 thoughts on “Lessons from: With a Smile and a Gun”