A few years ago, I wrote this post about my go-to questions to ask playtesters. The last one was this:

What do you think should happen? This is more of a question during games, but it still is one of my favorite tools: if players run into a corner case and ask “so what happens now?”, even if I know what the official answer is, I ask them what seems intuitive to them. If they come to the right conclusion, great! If not, that’s okay… unless it happens all the time. And if you didn’t have an answer yet, it gives you (1) a proposition, and (2) some time to think about it. In that case, you know you’ll have to figure it out, and you just want to make sure it doesn’t break the rest of the test.

It still is my favourite question, and I do believe it should be used more often. That being said, I would like to amend that paragraph in a few ways.

First, I changed the wording from “What do you think should happen?” to “What would you like to have happen?” The former often had testers resist: I think part of it is some people understand it as a quiz of their memory of the rules I taught, also because it suggests there’s a right answer, and with it, a chance they get the wrong answer. It also asks them to think of rules, of why they exist, of interacting systems: not everyone likes to do those things. In a way, it also positions them as an expert, which while some people enjoy, a lot feel intimidated by.

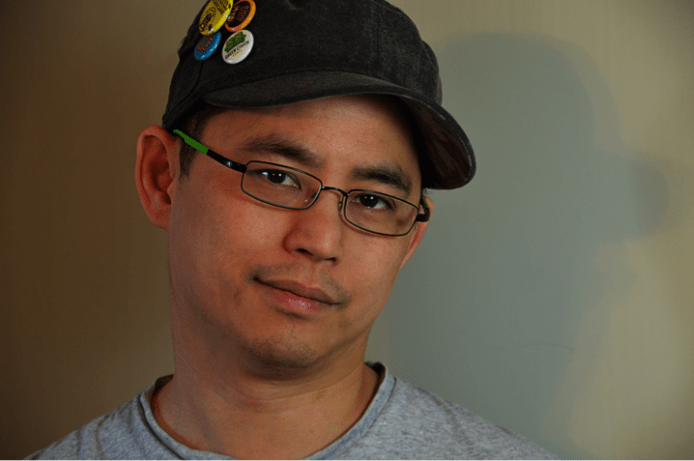

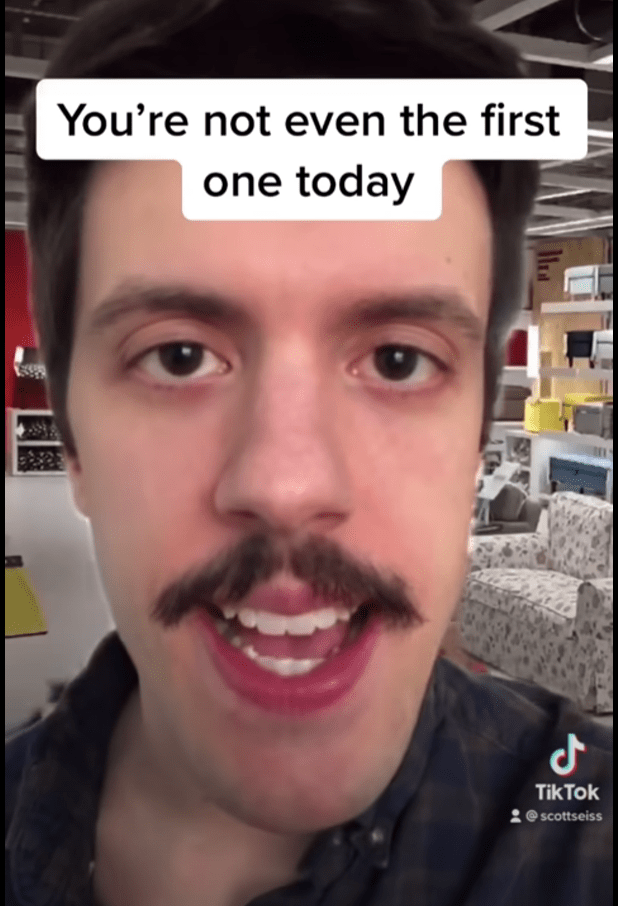

On the other hand, “What would you like to have happen?” is 100% subjective, no wrong answer, no experience required. I have yet to find a playtester who didn’t have an answer to it, although sometimes you get a “oh I would like for this to give me a million dollars”, which forces me to bring out my retail worker face from 2006 when people hit me with a “Oh, it didn’t scan, it must be free”.

That switch is also a parallel to the adage “playtesters are great at telling you problems, but poor at giving you solutions”. I trust playtesters to tell me how the game made them feel, but less so to analyze how to make them feel differently. When I ask “What should happen?”, they often start brainstorming: “oh, this could work like in Terraforming Mars” does not solve the problem of “what do I do when I land on my opponent?”, it just opens up a discussion that takes away from the playtest. When I ask “What would you like” and they say “I think I should get a bonus in this case, it’s so hard to do”, it means they feel like the game doesn’t appreciate their achievement enough. That’s a direct screenshot of their emotion.

In other words, once I know how the players want to feel in this situation, I can figure how to get to that result on my own.

The other reason to return to it is that I also want to nuance the reasoning behind that phrase. My design process has changed a lot over the past few years, and now I treat playtests, especially early ones, as much more exploratory. I come to playtests with an incomplete ruleset. I change games on the fly a lot more. I leave rules ambiguous on purpose. I use different icons or terminology to represent the same thing, just to see how players react to them, which ones stick and which ones don’t.

Which means players ask me a lot more questions, and more importantly a lot more questions to which I have no answer. In that post, I said I wanted to see if they’d guess the right rule: I still think that’s a useful way to gauge a rule’s intuitiveness. However, that doesn’t apply to my current design process. When people ask a rules question, it’s often a Schrodinger’s rule: until they guess it, there is no right or wrong. When they guess it, based on how much it messes up everything else (a process I discuss in this post), I can decide whether I say “sure, let’s go with that”, or pretend there was already an existing answer that I make up on the fly.