Every now and again, I manage to play games, sometimes even play new ones, sometimes even good ones! And when I do, there’s often one mechanism that just sticks with me, a mechanism that I think about in the shower, in the car, in front of the fridge… This is what the SISIGIP series is about: Stuff I’d Steal in Games I Play.

Many games have multi-use cards: I’d even say it’s one of my favourite mechanisms. One of my own games, Mapping the World, uses it. Multi use cards have a lot of pros: first and foremost, they make decisions richer through the power of combinations, but also, they help mitigate random card draw, like in Race for the Galaxy (RftG), where you pay for stuff by discarding cards. Actually, “card as money” has been used in many different games, often with some twists, like in Bloody Inn, Summoner Wars, or even Gloomhaven.

Well, Dollars to Donuts takes it one step further. Dollars to Donuts (DtD) has multi-use Dollars.

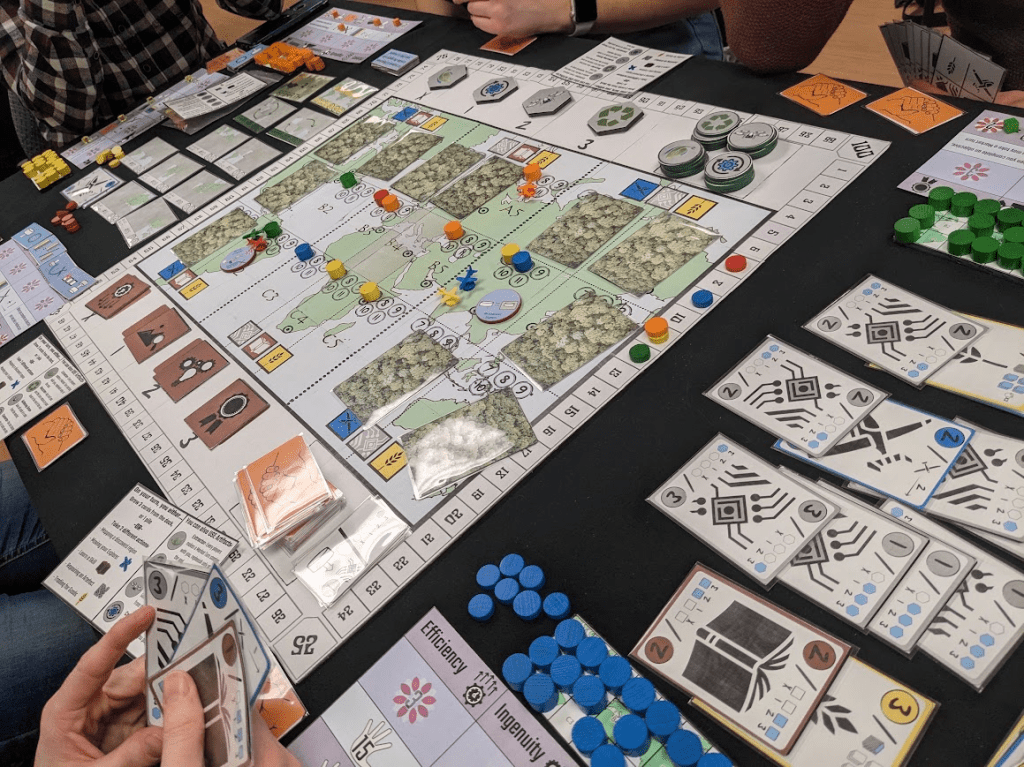

Dollars to Donuts is a tile laying game where you try to match donuts to gain points, or mismatch them to get money. Money is mostly used to buy tiles from a river-style display with diminishing cost. However, the special thing is that Money is a square tile. On one side, it shows a dollar, and on the other… well, it’s a tile, just like any other tile in the game.

Where Donut tiles are 1 square wide, but 4 squares long, Dollars are a 1×1 tile, which can be used to go in and patch holes, or sometimes just give you more of a chance at the one donut flavour you’re looking for.

A Question of Perception

Mechanically, it is no different than the cards in RftG. Both can either be used individually for what they show, or spend in bulk to pay for stuff. What makes it different is how it is presented. In RftG, you draw cards, but any uninteresting card you can discard to pay for your tableau. In Dollars to Donuts, you gain money, and you can use a money tile to play in a gap. In RftG, the default is the card face; in DtD, it is the dollar.

However, it’s not just a question of labels, although the label is indeed important. It’s about which use is the main focus of the item.

In RftG, the point of the game is to play cards to your tableau: sure, most of the cards you draw will be discarded, but when you draw, you have to select which cards you’ll try to play, and the tension in that is what makes the mechanism.

In DtD, when you gain money, you usually do so because you intend to use it as money. When you look at the backsides, it often is an afterthought. Sometimes, you have matching donut holes (which score in pairs), or a small space on your board, or a donut flavour you can’t match from the market: then you look at your dollars, but they are dollars first. Because the odds are such, the most common emotional reaction to that draw is a pleasant surprise when you get a useful tile, not the disappointment when you don’t.

To be clear, I understand it’s not groundbreaking. A lot of what we consider innovative game mechanisms nowadays are less completely new systems than just presenting classics in a new, original way.

What does it do well?

In many games with money, you stack it, then spend it. Budgeting is a very rich strategic dimension in and of its own.

In Dollars to Donuts, your relationship with money is different. Every dollar you make is like a lottery ticket: will it be the tile you need? Sometimes, you have 5$, but 2 of those dollars you want to keep as tiles: the decision on whether or not to spend 4$ is much more interesting, because adding that factor makes any two potential moves much harder to compare, which makes it more interesting (LINK).

Every dollar being unique also has an interesting impact on how you spend. Also, where in most games, money is a zero sum thing, in Dollars to Donuts, spending 5$ to gain 5$ is often a great move, as those are 5 new shots at getting a tile you need. Therefore, it makes people hoard less, and makes that economy more dynamic.

How would I use it?

I don’t think it’s a mechanism that requires much modification: aside from changing which actions are linked to money tiles, there isn’t much we can play around with. It’s also not a mechanism you can build a game around as much as just one you include in a game to make a part of it more interesting (EDIT: Since I wrote this, I played Salton Sea and was proven wrong. You can definitely build a game around this).

Like I said above, the mechanism disincentivizes hoarding money, making the economy more dynamic. In a way, it can help with the Healing Potion effect. I have a few prototypes I’ve worked on where I’d like to give people an avenue to use up their money without adding a new mechanism to the game, and so I gave them a try.

Two pitfalls I identified when using this mechanism (and by identify I mean “fell right in, face first”) are that those effects have to be (a) simple, and (b) not add new rules. There’s a side mechanism in Mapping the World which had bothered me for a while, a currency which people were getting but hoarding. I switched it up to individual cards with their own effects… and now players got confused about what the tokens did, and what about this one, wait, is that different from X?

The next time I use a mechanism like this, I will try to keep the effects simple: spend this when doing action X to gain more stuff, or at a lower cost, that kind of things. No new mechanism, no nuanced effects of “this might make it better”, just a clear “when you do X, use it to do more”. Using your money cards for the boost is the interesting decision point, you don’t need to be cute with what the effect does.