A large amount of game ideas I get revolve around a cool action selection mechanism (CASM, for short), which is a pretty popular subset of Euro games. However, when it comes to building out the actions for your CASM, there’s a pretty difficult line to toe: if they’re too similar, the CASM’s interesting decision space becomes a non-decision, but if they’re too different, you have too many subsystems to teach. Too simple, and the game becomes rote, but too complex, and they take the focus away from your CASM. You need to add variety without adding headaches. It’s quite a tricky tightrope, and it can quickly lead you astray.

This is the second installment in a series about CASM-focused games with an original system that gives you actions to add meaning to your core CASM and opens up the design space for more content, without adding too much rules overhead. It’s sort of a sub-series of SISIGIP (Stuff I’d Steal in Games I Play).

As a disclaimer, I want to point out that a game is not just a pile of mechanisms of systems. A game tells a story out of interesting moments, which come out of interwoven mechanisms. You can’t just take your CASM, plug in all these actions and call it a game. This is meant to be praising and analyzing excellent design, which can hopefully serve as inspiration.

Debts!

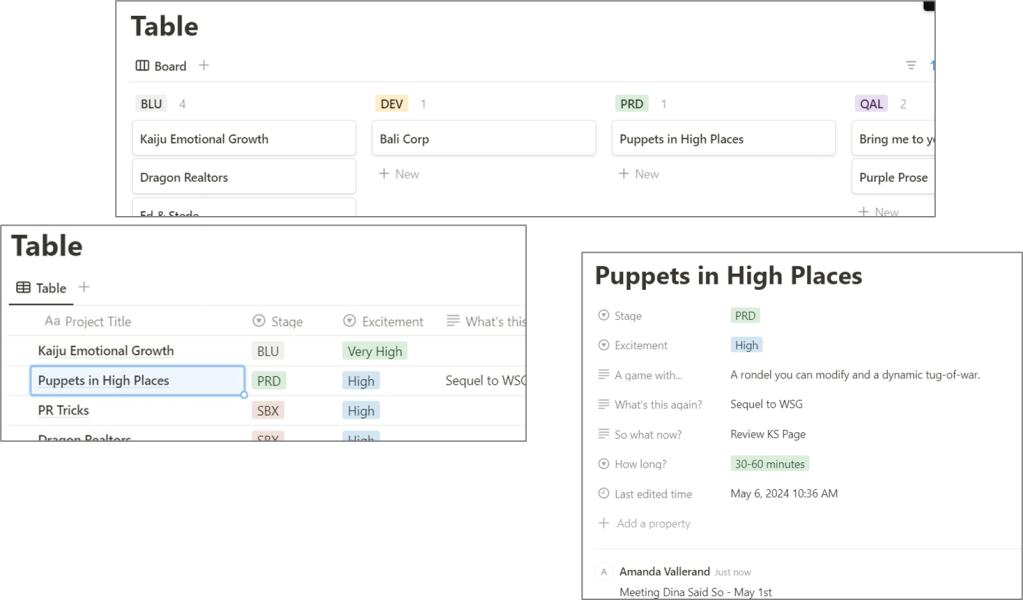

Garphill Games’ West Kingdoms trilogy is tied by its setting of medieval France, by its recurring characters, but also by its interesting Debt mechanism. While every game has its own twist on how they work and how they interact with the rest of the game, they all have a similar starting point: some actions, whether because they are too powerful or as a way of bypassing their cost, give you a Debt card. Debt cards cost you a handful points at the end of the game, because debts are bad, you see… or are they?

Each game also includes an action to Flip a Debt, which is much rarer than gaining Debts. Flipping a Debt not only rids you of the negative points, but also gives you a small immediate bonus, because paying off your debt increases your credit rating or whatever its equivalent is in medieval France.

One of the game, Viscounts, even went further, giving us Deed cards, a positive equivalent which you can spend a Flip action on to make it go from 1 to 3 VPs.

I find this mechanism interesting because not only is it incredibly simple and fitting in the series’ focus on corruption and virtue, but also because gaining a Debt card is both a cost (-2 VPs), but also an opportunity (using a flip for a resource). Gaining a Debt card is an unvertain value: you can’t know whether you’ll have time to flip it or not, nor how much you’ll need the bonus. That Uncertainty means you can’t perfectly math out the result, which makes the decision more interesting.

It also opens up so much design room. It adds three actions (Gain a Debt, Gain a Deed, Flip a card) with a single rules, and those actions are of different value, which opens up the possibilities of combinations to interesting places by offering a way to balance outlier actions. Maybe getting 1 Gold per worker is too strong, but what if we give you a Debt for it? It adds an interesting dimension to your design space.

Now, what if you built a whole game out of this mechanism?

Bones!

You’d get Good Puppers (also known as One-Deck Puppies after the publisher’s more popular game series), one of my favourite little card games in existence. Now I know this is a stretch for this series: this isn’t a “filler” action, it’s literally the entire game. However, counter-argument: it’s my blog and I do what I want!

In One-Deck Puppies, you play doggo cards to piles of other doggos of that race. Card backs have a Bone value on each side: 1 – 2 – 5 – 10, to say how many points they’re worth.

The game revolves around 3 actions: Bury a bone (place a facedown card from the deck behind this column, showing the 1-value bone), Flip a bone (increase it to its next value), and Move a bone (send it to a different column). The first two are conceptually equivalent to the Debts and Deeds we discussed above, although the Flip has the extra boost of having 4 values per card, instead of 2. The Movement, however, adds a LOT.

You see, a bone’s location can come up in a lot of different ways. It’s never just Flip a bone, it’s Flip a bone here, or Flip a bone under each column with X amount of doggos, or Flip half the bone in a specific column. It’s never just Bury a bone, it’s Bury a bone in every column without a Bone, or Bury as many bones here as you have doggos. Moving the bones to the right place can set up combos in a very, very satisfying way.

Both Debts and Bones are examples of resources which are also opportunities, which can make a game’s decision space richer and more nuanced without adding much rule overhead. It’s a simple system, but one rich enough to literally build an entire game around!

Can you think of another game that features a similar resource that is also an opportunity for a better result?